The Global Food Crisis 2007/2008

Global food production is vulnerable to weather, pandemic, political and economic shocks. Supply shortages in interconnected food systems can cause food price spikes around the world, as illustrated in the Global Food Crisis 2007/2008 when cereal prices more than doubled in many areas, causing humanitarian emergencies as well as promoting political upheavals (Heady & Fan, 2010; Johnstone & Mazo, 2011).

In the UK, the consumer price index for food rose by 19% within the two years of the crisis – the highest increase in the last 30 years (ONS, 2019). Even though UK consumers spend a relatively modest share of their total expenditures on food (Eurostat, 2019), data on nutritional health, affordability, trade balance and ecosystem health, indicate latent vulnerability in the UK food system.

Average diets are nutritionally poor

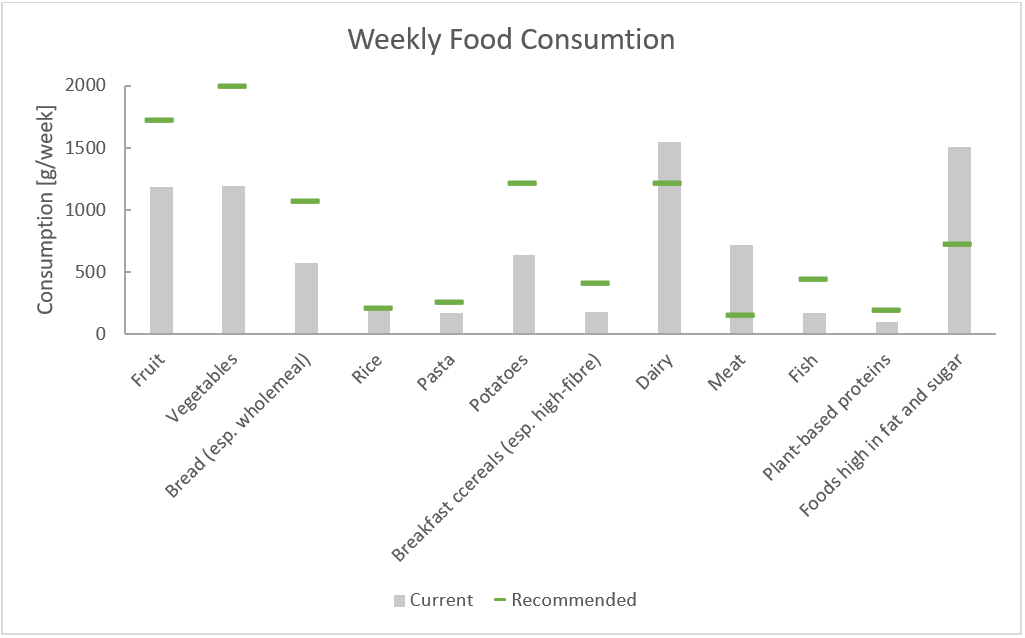

A comparison of current food consumption with government dietary guidelines (Public Health England, 2018) suggests malnutrition risk. Figure 1 displays current average consumption levels in relation to a nutritional optimum.

Figure 1: UK average food consumption 2008-2011 compared to the governmental dietary guideline (adapted from Scarborough et al., 2016, p.6, who base their values on an optimisation model minimising changes from current consumption patterns to meet the government dietary guideline)

UK consumers under-consume fruit and vegetables, high-fibre carbohydrates, fish and plant-based proteins, while over-consuming dairy, meat and fatty and sugary foods. A recent health evaluation estimates that 14% of deaths in the UK are associated with poor diets (Lancet, 2019), and survey results indicate that levels of obesity and overweight levels amongst UK adults range between 60% in Wales (Public Health Wales, 2019) and 65% in Scotland (Health and Social Care Scotland, 2018).

Is healthy food affordable?

Several factors explain unhealthy diets, but affordability is the most relevant factor in terms of consumer resilience. This has been investigated by the Food Foundation (Scott et al., 2018) using UK household survey data. Their results suggest that the wealthiest half of UK consumers need to spend 12% of disposable income on food in order to meet the dietary guideline, compared to around 28% for the half on lower incomes. For the lowest income decile, this figure increases to 70%.

These findings underline why nutritional security in the UK should not be taken for granted, especially in households with lone adults and households with children. Fruit and vegetables – for which consumption is strongly related to income level – are particularly likely to be under-consumed when incomes are low (De Agostini, 2014).

Food supply is dependent on imports (from the EU)

Government data shows that the UK food trade deficit has been increased over the last 25 years. Figure 2 shows trade balances for eleven major food groups.

Figure 2: UK trade balance in 11 major food groups (adapted from DEFRA, 2019, pp. 89-90)

Imports exceed exports in every food group except beverages. Fruit and vegetables are the largest food import commodities by value (£ 11 112 million). The largest import commodities by volume include cereals (5.3 million t), fresh fruit (3.7 million t) and fresh vegetables (2.3 million t) – all of which are under-consumed. 70% of the food commodity imports displayed in figure 2 originate in the EU, while 62% of the exports are sold to the EU (73% when disregarding beverages). In other words, the UK food system is dependent on trade, the majority of which arrives from the EU.

Domestic production focusing on products that are excessively consumed

A Morrisons supermarket study in 2017 showed that even if exports were halted, the UK food system would only achieve 61% self-sufficiency (Benton et al., 2017). Furthermore, domestic production is not in a position to reduce the nutritional shortages in fruit, vegetables and carbohydrates. With a total output of £14.8 bn. in 2018, livestock agriculture is the most economically significant agricultural sector in the UK, generating 57% more turnover than arable production (DEFRA, 2019). Half of the available wheat in the UK is used as animal feed (AHDB, 2019). While livestock production may be an economically efficient land-use, it does not contribute to mitigation of the nutritional insecurity.

Environmental conflicts

Unsustainable food production constitutes a driver for ecosystem depletion, due to the release of greenhouse gases, pollution of soils and waters with nitrogen and phosphorous inputs and threats to biodiversity (Springmann et al., 2018). According to the UK National Ecosystem Assessment (2011) domestic natural ecosystem services in decline include vegetation, fish, water supply, species diversity, hazard and disease regulation, pollination, detoxification and purification of soils – large parts of which are linked to food production. While the national impacts are significant, 70% of the cropland impacts and 64% of the greenhouse gas emissions from food production for UK consumption are located abroad (de Ruiter et al., 2016). Achieving food security in the medium term implies that environmental conflicts will be resolved both within the UK and beyond its borders.

Consumer resilience

Resilience analyses of the UK food system need to focus particularly on import commodities such as fruit and vegetables, which ensure a sufficient supply of energy, fibre, carbohydrates and various micronutrients (Macdiarmid et al., 2018). Typically, identified risks include logistical bottlenecks associated with maritime transportation into the UK. Lang & McKee (2018) point out to food security threats associated with Brexit, as supply chains are vulnerable to e.g. regulatory misalignments, labour shortages, tariffs, impediments to transport and damages to production. Within the RUGS project, such threats are studied to find ways to increase food system resilience.