Lively discussions during the 2020 RUGS workshop

After two successful stakeholder workshops in 2017, 2018, we have conducted our final RUGS workshop in September this year. 31 participants with an exciting range of backgrounds joined the RUGS team to discuss UK food system resilience. Although this year’s workshop was conducted online, it encouraged lively discussions, interesting results, and useful feedback to the RUGS project.

FIgure 1: Background of Workshop Participants

An Interactive Workshop about UK Food System Resilience in Three Sessions

Organising this year’s workshop, we decided to bring together simulations of global shocks, observations about the food system during Covid-19 and some ideas on how to increase the resilience of the UK food system in the future. We conducted the workshop in three sessions, including presentations, interactive activities and alternating breakout groups that allowed for focussed discussions between the participants. A multitude of perspectives and areas of expertise provided excellent outputs.

Session 1: Simulated Global Shocks to the UK Food System

This session was based on previous workshops, where stakeholders had developed storylines of shocks to the global food system, which would have an impact in the UK (see Hamilton et al. 2020). We simulated four of these shocks in our PLUM modelling framework, and presented the results to workshop participants in order to see whether expectations were met and what our model might have missed.

The simulated shocks included (1) a cyber-attack on highly automated and efficient food systems, (2) financial speculation divorced from production impacting wheat prices, (3) a pathogen wiping out soy bean crop in Latin America, and (4) a doubling of import trade tariffs for food in the UK (protectionism). Quantifying impacts on UK consumer prices, UK production quantities and UK land-use, we showed food system resilience consequences at different levels, i.e. households, producers and environmental sustainability.

Here is how our modelled results matched stakeholder expectations.

Figure 2: Participant feedback on “Do the modelled results match your expectations?”

As evident in figure 2, our modelled results largely met stakeholder expectations (100% in shock 1 and 2, 92% in shock 3, and 82% in shock 4). We also received helpful qualitative feedback and ideas on how to improve and extend our model. Main suggestions included to consider nutritional implications (micronutrients) of shocks in more detail, to assume a wider range of improved technology scenarios, to consider diet shifts to reduced meat consumption, and to consider other efficiency measures next to cost-efficiency in the food system.

Session 2: Market Power and Food System Resilience, as Shown During Covid-19

The central question of session 2 was: Does market power increase or decrease food system resilience? In order to provide a context to this question, we started by discussing Covid-19 to see what parts of the UK food system are considered vulnerable by our workshop participants. Figure 3 illustrates the results; word size indicates the frequency of responses.

Figure 3: Participant feedback on “What parts of the UK food system have been affected by shocks or disturbances in recent years?”

Stakeholders see a particular vulnerability at the consumer end of food supply chains, although intermediate levels and the producer end have also been mentioned repeatedly.

Splitting the full group of stakeholders into smaller breakout groups, we initiated discussions about recent shocks such as Covid-19, and how market power played a role in mitigating or exacerbating the impacts of these shocks on food supply. Market power is associated with reduced levels of competition in concentrated markets, and this is typically considered detrimental by economists, as it is expected to increase profit margins at the expense of consumer welfare, producer welfare, and sector efficiency. While many see market power intuitively as a bad thing, however, its impacts on the resilience of food supply can cut both ways.

Several cases were mentioned and illustrated the multidimensionality of aspects involved. In spite of all ambiguities, the discussions confirmed that market power associated with very uniform processes and rigid supply chains, can reduce the adaptive capacity of firms to maintain food supply in case of a shock. Supply chains with a low functional diversity are considered to incorporate less redundancy and are therefore more vulnerable. For the majority of participants, this implied that concentrated markets are less resilient than well dispersed markets.

At the same time, market power rooted in coordination and cooperation can imply better adaptive capacity, as shown during Covid-19 when governments relaxed competition regulations in order to allow supermarkets to work together. Some participants also pointed out that fiscal capacity from higher profit margins can enable firms to buffer shock impacts to consumers. These resources to absorb shock impacts are unlikely to form in a fully competitive setting, where firms are working on the edge of profitability.

Power can enable firms to act in a benign way, and they might do so as long as it is in their interest. Participants agreed that monopolies are bad, but some pointed out that a few powerful competing retailers with diversified supply chains might be good for the resilience of food supply, as well as for low consumer prices. While consumers might be the winners of such a system, however, it could degrade producers to become the losers of the system, if they receive less pay due to retailers’ buyer power. There is a risk that vulnerability is simply shifted to where there is less power in the supply chain. Participants also referred to some small-scale producers during Covid-19, who were able to quickly shift their business model and supply their produce to customers locally. Small size might in some cases make firms more flexible to adapt to changing environments.

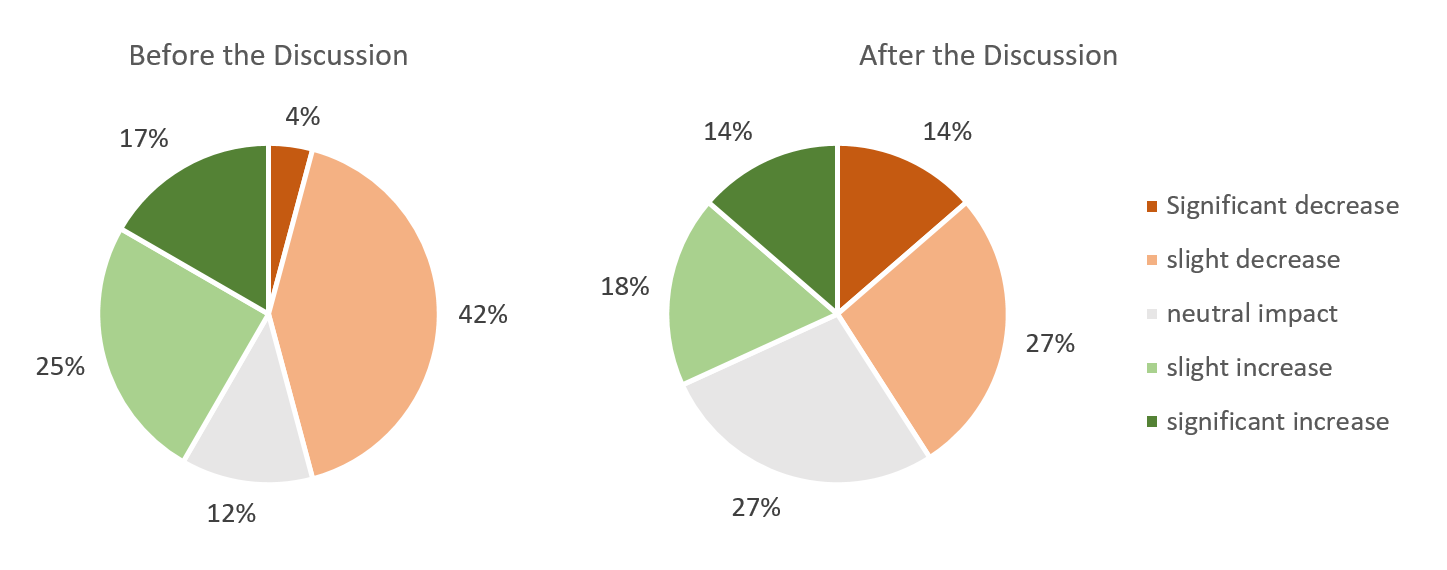

Here is what our participants thought about market power and food system resilience in general before and after the discussion.

Figure 4: Participant feedback on “How does market power impact the resilience of food supply?”

As we can see in figure 4, the general opinion was fairly balanced, although there was a slight majority arguing for negative impacts from market power on the resilience of food supply. During the session, several participants shifted their opinion towards a neutral impact.

In conclusion, the discussions confirmed that no general resilience impact from market power can be ascertained without detailed consideration of the diversity of processes, flexibility, redundancies, and accountabilities in the individual case.

Session 3: Actions, Mechanisms and Policies to Increase UK Food System Resilience

Building on the first two sessions, session 3 was used to draw conclusions for mechanisms, actions and policies that could increase food system resilience in the UK. We conducted this session in an interactive and informal way, starting with a survey of ideas.

The following list summarises suggestions to increase UK food system resilience as submitted by participants.

Increased policy coordination across UK regions, institutions and departments as well as better understanding of the food and drink industry within these departments.

More redundancy in the UK food system and creating increased food stocks, e.g. launching a national food storage policy. There should also be a government support system for times of crisis.

Improved nutritional security, especially for low income groups, e.g. by introducing an improved benefits system or having a state-funded provision of fresh produce.

More flexibility in the food system, e.g. a policy to improve retailer flexibility.

Better cooperation between businesses, e.g. a policy to improve relationships between small and medium scale businesses.

Enhanced diversity of actors at various levels of the supply chain, specifically a diversified and robust supply base.

Maintaining supply chains from overseas by strengthening bilateral relations.

Maintaining and enhancing domestic production (as a priority to free-trade agreements that threaten domestic producers). Support to domestic sourcing of food and simplified supply chains.

Reducing food loss and food waste; facilitating the repurposing of unused food in the foodservice sector.

Promoting agro-ecological production approaches, e.g. support for agroforestry, and a procurement policy to focus on sustainable options. Welsh Wellbeing of Future Generations Act can be taken as a model.

Education and transparency to increase public understanding of seasonality of produce. More information on where food has come from and how it compares to healthier and/or cheaper alternatives.

Better skilled labour force.

Research to

recognise efficiency – resilience trade-offs

focus on systemic resilience instead of individual aspects

understand how financialisation impacts food system resilience

analyse how climate change will affect suitable crops to grow in a warming climate

investigate to what extent resilience relies on state capacity to intervene in case of a shock and whether this is impaired by anti-Big-State attitudes.

A subsequent breakout group session allowed for deeper discussions of these ideas amongst the participants. The task was to develop a 1-minute “sales pitch” of an idea that the group could agree on. Back in the plenary, every sales-pitch was presented and participants allocated points to the presenters. The winning pitch (39.4% of the votes) advocated for the creation of a “National Food Service”, providing free nutritious food to people in need, in relation to their income. Surprisingly, the second-placed pitch (36.8% of the votes) also prioritised nutritional security of food in the UK.

This result suggests that the workshop participants considered poor diets and accessibility issues to healthy food as the most significant problem of the UK food system as it currently is.

What Next?

The workshop was very useful in providing feedback to our current work in the RUGS project as well as highlighting what stakeholders would like us to focus on in our future work. As immediate outcomes of the workshop, we are preparing two publications which will include stakeholder feedback to our global shocks simulations as well as to the interactions between market power and food system resilience. We will circulate these to all our workshop participants in the coming months.